the destroyer > cheap papers > Maureen McHugh

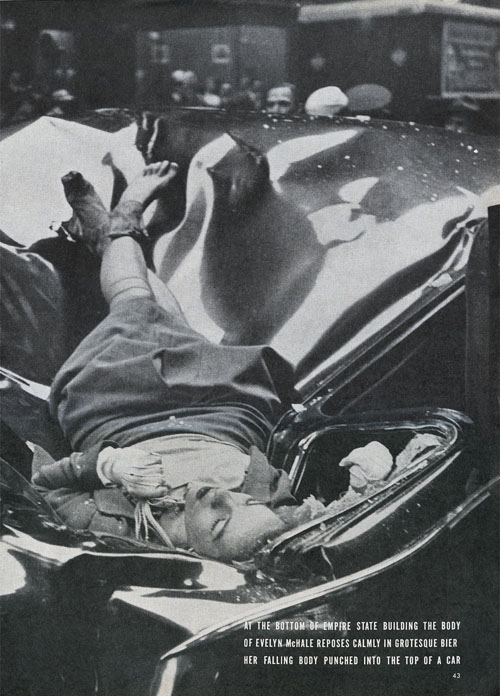

Originally published in Life magazine in 1947, the photograph of Evelyn McHale, taken immediately after her death, has been described as "the most beautiful suicide" [1]. That McHale is dead in the photo is hardly obvious. There is a certain [dream-like] quality to the image: the fracture of glass staged-looking, the expression peaceful, her body laid out in an intimate position. McHale looks incredibly beautiful; a beauty which is primarily responsible for the overwhelming interest in the photo, as many describe the power of the photo lying in the fact that "one cannot look away," citing the transfixing nature of the photograph. There is the need to watch, to see, despite the fact that Evelyn's beauty is pressed up against the image of her own death. Observers, it seems, can only hope to achieve this type of beauty; a beauty which is dangerous in the way that all fantasy is dangerous // in the way that all fetishization (observation) is inherently false. The suicide note found in her purse read: "I don’t want anyone in or out of my family to see any part of me. Could you destroy my body by cremation?"[2]

///

Though her body was cremated after identification, the image of Evelyn has been viewed, re-contextualized, & transmitted a countless number of times. Through this visual "re-telling" it has reached iconic status, though it is through this re-telling that the life has been stripped of its individuality, its backstory [hardly any facts are known about Evelyn], its essential human-ness [as I am calling it]. That the body can be destroyed yet remain eternal is important here, even despite one's own explicit wishes

///

///

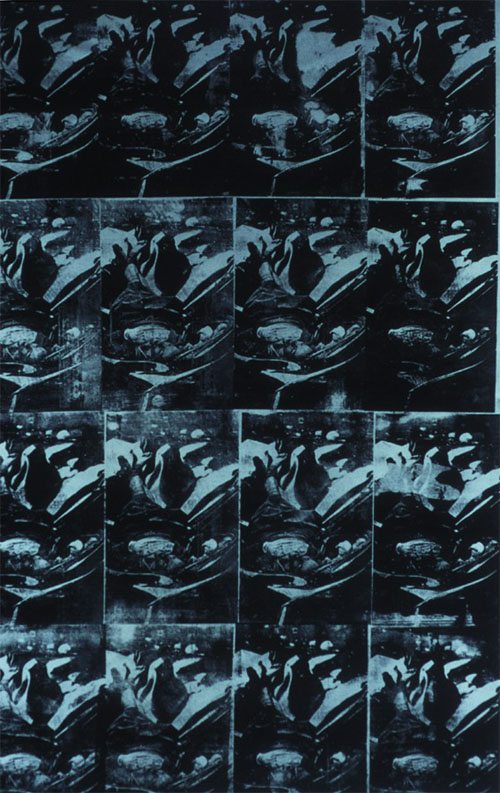

Andy Warhol appropriates this image in his Death and Disaster [3] series, though alters it through a change of color and through the repetition of the image again & again, a fascination both with the death itself and the particular place this death holds in infamy within popular culture. The photo becomes symbolic, stripped of meaning, or rather full of many meanings, repeating endlessly: [//WOMAN / DEATH / SUICIDE / VIOLENCE / BEAUTY//] (you choose). The image has been commodified, repackaged, re-purposed. The representation is removed many times from the actuality of the life behind it in the service of meaning-making, stripping it of its intimacy, its privacy: death imitating life; art imitating death

/////////////////////////////////////

The 2014 film Nightcrawler focuses on the main character Lou, played by Jake Gyllenhaal, as he establishes and profits from selling footage of crime-scenes to a local Los Angeles news station. It is not particularly through brutality that Lou succeeds [though there are absolute shades of it, as he moves bodies to get better shots, enters homes illegally to provide the perfect framing for the tragedy], but rather through a disconnect; he is unable to view the bodies as Real, unable to see them as anything beyond the symbol that they represent [//MONEY / POWER / SUCCESS//] (you choose.) The film is concerned with capitalizing on the tragedies of others, and the currency of observation which death works within; the almost commonplace level of blankness, disconnect, and apathy with which the maker creates and the viewer consumes

////

At a moment in the film of particular self-referentiality, Gyllenhaal's character comments on his intent, stating: "I'm focusing on framing. A proper frame not only draws the eye into the picture but keeps it there longer, dissolving the barrier between the subject and the outside of the shot" [4]. The commodification of the tragedy of the body becomes artistic; it becomes a place for the viewer to transcribe their wishes over the observed image, dissolving the body of the other // replacing it with the desires of the self. There is a perforation between what is owned by the body in the image and what the viewer believes they own or wants to own, simply because they have access to it. This artifice draws currency: both literally and emotionally, though this currency is often fleeting. But beyond exploitation, there is a sense that this is what all art does, has done, and should do, that this commodification is both expected and required. The message is clear: that there is an inherent violence in observation

///

The series Black Mirror [2011], gaining quick popularity within recent months, explores a multitude of realities that the viewer could easily prescribe to a not-so-distant future. Episodes focus mostly on the self-punishing, sadistic, or masochistic aspects of technology, the world of over-sharing, and the desensitization to the idea of being seen or wanting to be seen. Often the line is blurred between the two, where characters are forced to be observed, to re-call, or are forced to submit to punishing tasks publicly, with all aspects of themselves exposed, all senses of self-hood (human-ness) abandoned. There is an undercurrent of violence throughout the series, both obvious and subtle, implicating the invasiveness of technology not as functional, but rather as self-damaging and expository. The series presents a reality which seems exaggerated but rings true: that the act of being seen becomes one of self-torture. Further, the show asserts that the act of exposure is a dangerous task which one is being asked to complete constantly. The true brutality, though, lies in the thin barrier between the self and the image represented, the image consumed mindlessly, met with an apathetic, disaffected reception, no matter how brutal this exposure is

////

// I // DON'T // WANT // ANY-

ONE // TO // SEE// /////////////

ANY // PART //

OF // ME ///////////////////////////

////

Place art up against reality: the difference has become indistinguishable. There is a sense of numbness in this over-exposure, the need to share, to document, which is becoming, progressively, more and more of a requirement. There is a brutality in apathy, as the viewer watches from their homes, then quickly changes the channel, or scrolls endlessly through feeds which feel infinite, hardly emoting. The viewer is not required to empathize deeply, though still asks that the image expose itself indiscriminately. The pain of the other gets erased when seen through a lens, as all is seen through a lens, and a disconnect follows. One positions one-self to consider all things they do as though they are being watched: as though a camera is attached to the body, invisible and seamless. A lack of privacy is transcribed, inherent, internalized. The body enters the world, always open, positioning itself to be seen, to open everything, then to be disregarded

[referenced]

[1] http://time.com/3456028/the-most-beautiful-suicide-a-violent-death-an-immortal-photo/

[2] http://www.codex99.com/photography/43.html

[3] http://www.sothebys.com/en/news-video/blogs/all-blogs/21-days-of-andy-warhol/2013/11/andy-warhol-death-disaster-series-prestige.html

[4] https://www.scribd.com/doc/250889715/Nightcrawler-Script