the destroyer > reviews > Joe Hall on 'EVERYNONE'

THINKERSHIP? DESTROYERSHIP. (PART I)

A REVIEW OF ADRIAN PARSONS’ EVERYNONE

When Kenneth Goldsmith began to receive national media attention, critiques of the conceptual mode became inevitable1. While all this clockwork piling-on has me almost wanting to defend the virtues of this art that seeks to transform a readership into a thinkership, let me instead draw our attention to a work which both embraces, critiques, and extends the horizons of conceptual writing: Adrian Parson’s Everynone. This project was staged in Washington, DC’s Transformer Gallery from July 11-July 20, but in many ways, Everynone began and ended its relationship with the public well before and after these dates.

For several years Parsons collected in a Google Doc ideas for conceptual art projects, notes on art and politics, quotes sourced from various media, and the stray diaristic thought. The mass of notes includes proposals for building assault rifles from semen, manufacturing drones to deliver Zoloft, and injecting gold into his bodily tissues. The first step of Everynone was making this document available for manipulation by the public. Peppered with a wide range of references to family, friends, and artists famous and obscure, Parsons’ notes situate themselves as a product of intense social dialogue and influence. Its gregarious character marks it as the product of chance and association which helps bring participants into the act of manipulating its text. The opening of this document to the public also mark’s Parson’s own vulnerability in a way that replaces the conceptual artist as genius impresario of his or her own elegant ideas with conceptual artist as offspring, student, colleague, consumer, and friend. It stages filiation in a complex, open-ended way.

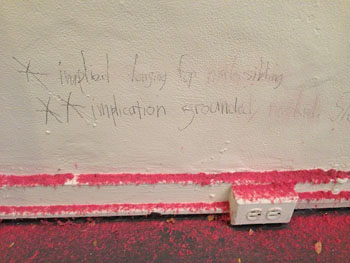

In the gallery itself, Parsons worked from this document, spending 24 hourxs translating this digital text onto the walls of DC’s Transformer gallery in various fonts, sizes, and lineations. His instrument was the no. 2 pencil. This was the least impressive aspect of the work. Parsons is not a master in graphite.

Like other visitors, I arrived to find Parsons still at work and a pyramid of 3,000+ erasers in the middle of the floor of the small gallery. We were invited to take the erasers and edit or erase the text on the wall while Parsons’ continued to transcribe. And we did. Parsons and the gallery visitors orbited around each other making, destroying, and re-making almost a decade’s worth of his concepts. At play with the process of selecting ideas to intervene into was the tactile joy of handling the pink erasers. With a dozen or so other sweaty participants doing the same, the show, at its height, took on a carnivalesque atmosphere, and, in a moment that seems ripped off from a Don DeLillo novel, a homeless man entered the gallery and began handing out erasers to unoccupied visitors. By close Adrian had been awake and working for forty-eight hours. Much of what he had written and conceived of had been erased, the baseboards covered in fleshy pink shavings.

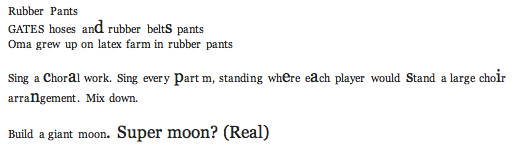

And the “original” digital text? In much conceptual writing, the result of executing the concept is almost beside the point. Christian Bök’s Xenotext Experiment, in which he proposes to write poetry in the DNA of bacteria, didn’t even have to happen to occur to make waves. The case is different here. After the walls were painted over, what was left of Adrian’s ideas remained in his muscle memory, the minds of the gallery visitors, and the re-sculpted google doc. Here is some text as of 8:12 PM, August 2, 2013:

While Everynone has received some attention from the national arts media, poets and anyone interested in the horizons of conceptual writing should take note. This is a stunning piece of conceptual writing: a record of reading, thinking, and destroying a career’s worth of pitches and abstracts, a poem made up of the distressed précis for conceptual art projects. In the play between its provocative ideas and curious, telegraphic textures, it is a pleasure to encounter.

Conceptual writing sometimes asks, “Why read the book when thinking about the concept is so much easier and rewarding?” In its multiple phases of presentation and experience, Everynone resists the drift toward concepts which can be communicated in under ten words (Instances of X in [famous/obscure work] Y are replaced with Z). Instead, Parsons’ piece seems to ask, “Why bother thinking about one concept when one sentence concepts are a dime a dozen?” A thinkership to receive ideas is replaced by a destroyership to wound them, to find purchase in the language and to intervene, enacting ones ethical or aesthetic values as a reader-artist-destroyer.

Beyond being merely an erasure, Everynone also offers its ideas for appropriation and enactment. That is, the gallery walls and the open digital document carry an undercurrent of direction or prescription akin to, in the poetry world, C.A. Conrad’s somatic experiments. Here is a version of composition where the artist structures a rich and evolving array of interactions, which, unlike a game, transcend any one field, real or abstract. If Adrian never places a “backpack bomb placed outside of a gallery…full of the artist's CVs and calls-for-entry,” he’d be happy if you did. Or if you erased the word “bomb” and followed your own directions.

[author's website]

1 See Amy King’s two part critique on The Rumpus (1 & 2), which is perhaps the most significant critique because it takes on both Kenny Goldsmith and Vanessa Place. Cal Bedient’s takedown in The Boston Review is more pithy but less thorough and ultimately less surprising. No one expects the people there to jump on board the conceptual writing gravy train. What is significant is that they bothered to respond. In turn, Robert Archambeau at the Poetry Foundation tried to throw a wet blanket on the whole debate in a quasi conciliatory article by examining in an almost comically self-professed neutral tone the strengths and weaknesses of conceptual poetry. Such a move levels conceptual poetry to just another exercise to try out when workshop gets stale. And then Kill List killed the rhetorical moment.