the destroyer > art > editor's introduction

IMPOSSIBLE CHOREOGRAPHIES

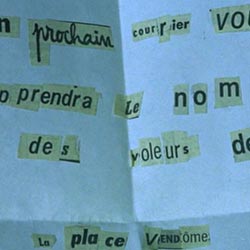

for Mark AguharA score: a text containing instructions for performance.

The beautiful thing about a score is that it never has to be realized. Rather, it is already realized, before its performance is even a possibility.

Yoko Ono made scores, meant to be completed in all kinds of ways. Her Prescription Piece from 1964 goes as follows:

Prescribe pills for going

through the wall and have only

the hair come back.

What does that even mean? I don’t really know. But it’s true, whatever it is.

I’ll admit to you now that I’ve been thinking a lot about the recent death of Mark Aguhar. For a while Aguhar was an art student at the University of Texas in Austin – an institution where I spend a fair amount of my time. She moved to Chicago to get an MFA. I’ve admired Aguhar’s work from afar; she made performances, videos and drawings.

The drawings: awkward hairy figures sucking each other off, or better, just standing in rows, and words painted in nail polish and eye-shadow seething a combination of sarcasm and honesty I can only call important.

One of her drawings from last year contains the sentence: “WHO IS WORTH MY LOVE, MY STRENGTH, & MY RAGE?” It’s a very good question. The drawing’s title: Not You (Power Circle). Even here, buttressed by the magic invoked on her own behalf, Mark was resolute in the question and furthermore confident in who was her audience. Not you.

Mark was transy. Queerish. A fucking fierce femme. And in the estimation of many of her friends a perfectly bright spot in the dismal and cold Chicago landscape.

My own way of coping is to imagine that Mark was performing the 1962 Yoko Ono score, Cut Piece: “Throw it off a high building.” It being her body. It feels cruel to write, and I’m sorry.

But then I remind myself that (1) suicide is not a score, (2) there is no reiteration when someone’s grown cold, and (3) it is near-impossible to find peace in art – instead it just mucks everything up. At least that’s what Mark’s work did for me: it clarified and cobwebbed. If there’s not peace, at least there’s comfort there.

A score: a text containing instructions for performance.

The tragic thing about a score is that it never has to be realized. Rather, it is already realized, before its performance is even a possibility.

Each of the artists in this issue of The Destroyer work through impossible choreographies, and have created their own scores, published here in lieu of artist’s statements. Much of this work, like the work of Mark Aguhar, is life-affirming and vainglorious in all the right ways. It is no accident that these artists produce and often disseminate their work in digital formats. Imbued with great intellect and humor, the work of Chloe, Rachelle Díaz, Lauren Klotzman and Jill Pangallo, proffer meditations/resolutions on the digi-physical body.

Facsimile, hits, coding.

Collectively, these four artists’ work make a forceful argument for living out a politics of the imagination, a need to halt disambiguation – ensuring the world is a messier place, for all of us. Outlining overlapping feelings that have no business sharing affective space is their particular bailiwick.

Chloe’s self-portraits dressed and prepped for clients (kept until now as personal artifacts stored on a digital hard drive) are as joyous as they are erotic, and Rachelle Díaz’s infectious Hippy Fit! photographs are a workout routine for the imagination , like weights on feather-light pillows. Lauren Klotzman’s videos inspired the theme of “Impossible Choreographies.” Her works are heady and elegant, maniacal and conceptually-tight models for living. Finally, Jill Pangallo’s animated .gifs function as digital age kinetescopes, looping at all-too-reliable speeds while purportedly documenting uncanny interventions in liminal spaces such as hotels. Those who look the other way when faced with her work are fools, plain and simple.

Did I mention looping, endurance, iterability, intolerability, and mutation are the lingua franca of score-ing? Of making this kind of work?

I will say this, what I have packaged here is easy to send to you a virus to send you: as useful as depression, as hard as a point-and-click presentation, wicked and obstinate.

A score: a text containing instructions for performance.

The fucked up thing about a score is that it never has to be realized. Rather, it is already realized, before its performance is even a possibility.

I have this image in my mind (it’s from my passssssst) of a tall and lanky red-headed dancer, wearing tea-stained underwear and an off-white sweater cinched at the cuffs and waist, propped up angularly against a highly-polished wooden floor –brightly lit, so his body is doubled in the gloss; he is a milk-and-red Rorschach realized in three-dimensions.

Here’s how I know it actually happened: I still feel my guts unwinding. Slowly.

I live for that moment… I re-live it... And I think it was actually meant for me, which obviously makes it imperative to use only one sentence to describe it.

I know from his Facebook that he doesn’t dance anymore – but knowledge really isn’t the same as Facebook, is it?

And another thing: what I know is often undone by the next day.

Since I asked all the artists in this issue to write out a score for you, I’ve written one too. I’m no slouch, but it doesn’t have a title. It is simply this:

Find a position you can’t get out of.

Then, free yourself.

––Andy Campbell